“The ma, or interval, is a basic building block in all Japanese spatial experience. It is functional not only in flower arrangements but apparently, is a hidden consideration in the layout of all other spaces.” - Edward T. Hall, “The Hidden Dimension”

A traveler is an audience of one, thrust into a story they must narrate for themselves. To make sense of a strange place, you have to map your confusions, in a hectic cartography that includes both the familiar and the foreign, what you recognize and what you don’t. We test ourselves as storytellers from the second we board a plane to the second we slump down on the living room couch. The mind’s map may be riddled with gaps or details of no consequence—an absurd TV show, an appalling lunch—but that’s fine. Memory may be imperfect, but experience is not. Lost in Translation, Sofia Coppola’s 2003 opus, is a film that not only captures the surreal subtleties of weary travel, but a piece that is in itself a journey impossible to fully recount, the real story residing in the spaces and details, its carefully placed gaps.

Despite the clumsy categorizing of the film as a romantic dramedy, Lost in Translation doesn’t rely on laughs, tears, or punches to get its point across, which I suppose is why some find it to be a gruelling watch—there doesn’t seem to be a point. No bullshit exoticism, no easy escapism. You don’t watch this film to howl at the hijinks of two ditzy lovebirds, nor to bawl at the melodrama of forbidden love. You watch this film to see how much the unspoken carries. How slow-burning hesitation, rather than abrupt consummation, can lead to a more mature form of catharsis. The partial victory you can believe in.

Bob, played by Bill Murray, is a fledgling middle-aged actor relegated to whiskey ads and flashy variety shows. There’s a tired woopty-doo to everything he says, sardonic and self-effacing. 25 years of marriage and all we hear of his family, for we do not see them even once, are their meager voices squeaking over the telephone. “They miss their father, but they’re getting used to you not being here,” his wife tells him late in the movie. Meanwhile, he is greeting untold millions at home through their TV screens, a tumbler of Suntory in hand, as if everyone in Japan were an ‘old friend’. All this when he could just be back in America, “doing a play somewhere”. Bob is getting paid 2 million dollars not merely to endorse a whiskey, but to be suspended in a sad tableau where he isn’t even center stage in his own life.

Charlotte, played by Scarlet Johannson, is a demure young newlywed, no closer to the good life despite her philosophy degree from Yale. Unlike Bob, who tries to deflect attention, Charlotte pines for her husband, a workaholic photographer, just to look her way; to see her as more than some out-of-focus figure floating from foreground to background. Jōganji temple, Shibuya crossing, Heian shrine; for a character that spends so much time navel-gazing, her itinerary boasts some impressive spots. But she never does seem quite fazed by these sights, only slightly bemused, wanting to be part of the scenery but not quite knowing how she fits. “There were these monks, and they were chanting, and I didn’t feel anything,” she says, confessing in a tearful phone call to a friend, as if she were expecting some secondhand religious experience; to be rocked to the core so at least she knows there’s a center. One that can’t be neglected or denied.

Our two leads are lost. With nothing to pull them forward in life, they are drawn together, by a shared lack of direction and purpose. Where to go next in the lives they’ve grown ‘foreign’ to? Or, in a more practical sense, where to go in the country they must become familiar with, where there are “no names on the streets” as Coppola remarked on Charlie Rose? Neither of them has a choice but to find shelter in inner monologue, in (often) drunk solitude and self-reflection, the only place they can be understood. What happens at the Park Hyatt could stay at the Park Hyatt.

But that tryst never happens. The movie is defiantly sexless, and the story takes place in a matter of days, confining itself mostly to environments dim or dark: the hotel bar, the insomniac’s bed, the ominous early morning. It’s a familiar setup: sly courtship, drunk infidelity, post-coital guilt. But Coppola veers from the formula, withholding the blows, and focuses not on some immature infatuation, but on the tensions just visible, the way the air in a room changes when someone drifts in through the door, the space indelibly altered; a hidden consideration, to use Hall’s phrase.

. . .

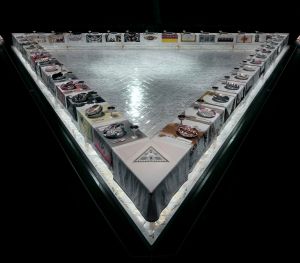

Ma is a Japanese concept of space, translated vaguely by anthropologist Edward T. Hall in The Hidden Dimension as “interval”, and at times likened to “negative space”. But this sense of space is not an absence per se, rather, a presence you can’t delineate. Ma is crucial to ikebana, the traditional art of arranging flowers, in ensuring a scene is not cluttered or incoherent. Two main styles of arrangement exist: tatehana (‘standing flowers’) and nageire (literally ‘thrown in’). The difference is not merely of presentation—the type of flower used, their ‘posture’—but representation as well. A carefully crafted “microcosm representing the entire universe,” or an exuberant expression of free will and personality. Even then, as Needleman writes, these “dual styles are not in opposition, but rather complementary, and to the Japanese eye, the other is always present even if not visible.”

This is where filmmaking and flower-arranging intersect—to do well in either requires a fine receptivity to space, a subconscious sense of something unseen yet palpable, and how to subtly arrange it. It is a form of practiced intuition, roughly translatable as subtext in the language of film. Indeed, a streak of paradox runs through this. Just as tatehana and nageire coexist invisibly at all times, a director must decide on what will be seen by the eyes and what will be embedded in the mind. It is a terrifying tightrope to walk, not for fear of falling, but that no one is even looking properly in the first place.

. . .

In other words, it’s the seemingly aimless detours that divides audiences: between the impatient and the curious, those who feel the story is getting lost and those who believe Coppola knows exactly where she’s going. Take the brief and tangential scene where Charlotte tries her hand at ikebana, wandering into a conference room where a few Japanese women are poised over vases. A lady in a kimono guides Charlotte to a vessel of her own and gestures for her to place a flower in it, insisting more than instructing. Charlotte chuckles and obliges.

Earlier that afternoon, sitting alone by her bed, she was smirking at the introduction of “A Soul’s Search,” a self-help CD that seems chock-full of discount Alan Watts soundbites. “Each soul begins with its own imprint, all compacted into a pattern that has been selected by your soul before you’ve even gotten here.” The next evening, as she’s cutting the tag off Bob’s tacky shirt before their first night out, he finds the CD and admits meekly to owning a copy. “Did it work out for you then?” she teases. “Obviously,” he replies, in casual self-deprecation.

Do you see it?

The tightrope?

Neither of them can buy into Dr. Rohatin’s new age spin on ‘predestination’. But in a sense, they were meant to meander on the path of disbelief—the CD really did work. Not as some pop psychology guide to self-actualization, but as a map that pointed two drifters in each other’s direction. Think of that single flower in Charlotte’s fingers, placed thoughtlessly into the vase, her naive trust in the hands of a stranger. It is a detail of no consequence, a scene so trivial that the story would lose nothing by its being cut. But in a movie that clings so close to reality, that insists that drifting is how we most often end up at any worthwhile destination, it might just be plausible that this scene, modest and brief as it is, is one of the rare occasions where Coppola is making clear to us that the inconsequential means the most.

And if this is the case, perhaps it means the inverse too: that the risks in Bob and Charlotte getting to know each other—the disparity in age, their marital commitments—are not really risks for these two people, who look not for lust, not even really for love, but for the lost comfort of likeness. Someone familiar in a foreign place, whose presence is a promise that you are not the only guest in this hotel flipping through the crazy channels late at night. Bob is glad to have found someone he can stand to be in a room with, and Charlotte is glad someone wants her there.

Let’s take it one further. Maybe it doesn’t even matter what Bob so infamously whispered into Charlotte’s ear at the film’s close. What matters is that it was said. The experience of travel is in itself a talisman, each memory a souvenir. In that inaudible instant, that carefully placed gap, we remember that people who have earned their love and brooded over its implications share something that is rarely excessive or ecstatic, but subdued, sacred in how long it took to get there. The meaningful silence, the shared space, where nothing seems to happen yet everything does.