Co-Authored by Graphite’s Arts and Culture Editors, Jacqueline Davidson and Laura Bertrand

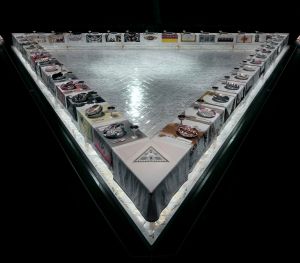

Feature Image, heartbreak places (#2), by Amanda Ventrudo

It had been a long week and there were three days to Valentine’s Day. We’re in the middle of a pandemic. We were tired. But we had plans to appear as reporters at a virtual poetry reading. We’d made the commitment, so we opened our computers and clicked the link and there it was: Mcsway Poetry Collective’s annual event, The Heartbreak Museum, and about thirty smiling faces.

In February of 2020, Mcsway, McGill’s only poetry club, hosted the second annual Heartbreak Museum. The event offered a physical space to display artifacts of love and artifacts of heartbreak—among them bongs, bottles, letters, photos, and poetry. In 2021, Mcsway was forced to move the event online. The collective’s Vice-President of Communications, Amanda Ventrudo, pieced together a webpage to showcase this year’s submissions. Poetry, videos, and journal entries appear in an all-too-familiar format as a threaded collection of the year’s loves and losses. Biographies accompany every piece, though some artists choose to remain anonymous.

From rooms in homes across the country and scattered around the world, the atmosphere was warm. If home isn’t a comfortable place, inviting this event into private space was a good way to make it so. As people settled into the event, the M.C. and president of Mcsway, Alana Dunlop, opened with a land acknowledgement. She called into The Heartbreak Museum from the “unceded territory of the Kanien’kehà:ka, also known as the Keepers of the Eastern Door.” She went on: “We have a responsibility as people who enjoy this land to acknowledge that it was taken from the Kanien’kehà:ka by colonial settlers, and that colonialism continues to exist in Canada today.” The tone and intention of the museum supports Alana’s declaration. At its core, The Heartbreak Museum explores acknowledgement as action. Can the act of talking about grief, raising awareness about our own pain and also the suffering of those around us, be an act of healing?

There was a lineup of poets scheduled to read. They performed work they’d written about heartbreak and by extension about the challenges that accompany an overwhelming sense of loss.

So while people performed acts of love and kindness around Valentine’s Day, sending gifts, and cooking candlelit dinners, Mcsway and the Heartbreak Museum chose to do the opposite. This was an exhibition of heartbreak, time to think about what inevitably accompanies love, the perils and true pain of heartache, a disenfranchised form of grief.

It’s tempting to consider heartbreak in the narrow context of monogamous, romantic relationships. This year of pandemic-related loss and isolation can be lonely, but our interview with Zeina Jhaish, Mcsway’s Project Lead, dispelled the myth that heartbreak is limited to ex-lovers. We asked Zeina what the goal was for the Heartbreak Museum this year. She said: “We want you to feel your heartbreak for whatever it is: family, friends, events, and, even, yourself.” With the aim of creating an accepting environment, the team behind Heartbreak Museum highlighted the importance of acknowledging the pressures that come with any holiday. The event seeks to reclaim Valentine’s Day. “People want to talk about what happened to them,” Zeina stated matter-of-factly on our call.

And so Mcsway succeeded again in creating a safe space to talk candidly about what heartbreak is and how it hurts. The event this year was particularly charged as we are all reckoning with the predicament of grief in a grieving world. In a notable line, a poet asked the audience:” “Isn’t truth an antibiotic?” Isn’t honest discussion about heartbreak the only path to healing? Mcsway’s Heartbreak Museum is important because it gives the heartbroken and the lonely an opportunity to use Valentine’s Day to talk about love in the most honest way they can, with poetry.

Jacqueline Davidson is a person from Montreal, Quebec. Jacqueline holds a bachelor’s degree in literature from McGill University, currently works as a freelance copywriter, and serves as the arts and culture editor here at Graphite Publications. Her forthcoming book, Memes as Artifacts: The Last Mango Pod in Manhattan, is scheduled to be published later in the decade.

Laura Bertrand is a Montrealer—de souche. Currently a junior at McGill University, majoring in English Literature, her interests include Canadian poetry, 20th century literature, and short stories. Also, keeping French and English far enough apart to finish a sentence in one language. She is a seamstress in her spare time, along with volunteering for social justice causes in the Montreal community.