“Colonialism is not a thinking machine, nor a body endowed with reasoning faculties. It is violence in its natural state, and it will only yield when confronted with greater violence.” - Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, 1961

The opening words of the essay film, Concerning Violence, cut across the screen like a sharpened, crude bayonet. Our attention has been caught; continue, we are intrigued. The camera follows a group of soldiers, rifles hung over their backs, walking through columns of elephant grass, the rhythm of the music carrying them forth, and our eyes with them. We are invited into a violent word, the dusk of the colonial world, where the bayonet speaks loudest.

We would be mistaken, however, to consider this world a thing of the past, and ourselves, the audience, as merely intrigued spectators. We are all actors in the drama that has unfolded, and which consistently continues to play itself out.

Olsson, Spivak, and Fanon’s Legacy

Göran Olsson’s latest film, following his retrospective piece on the Afro-American Civil Rights movement, Black Power Mixtape, is both an archive-driven documentary and an exploration into the mechanisms of decolonization. Concerning Violence brings to life Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth by collaging his text with powerful scenes from the struggles of decolonization in sub-Saharan Africa in the 1960s and 70s.

The film is constructed like an essay or book, divided between a preface, chapters, and a conclusion. In the preface Gayatri Spivak introduces Fanon and his work, contextualizing the 78 minutes of unorthodox translation of academic analysis to cinematic documentary that follows. So who is Fanon?

Fanon was born in Martinique in 1925 and was raised a “gentleman of the French empire.” He went on to study and practice psychiatry in France. His rejected thesis-turned-book Black Skin, White Masks marked the beginning of his quest to understand and resolve the dehumanization of the coloured man. Fanon made it his responsibility to assume the universalism which he believed to be inherent in the human condition.

In the mid-1950s Fanon joined the ranks of Algeria’s National Liberation Front (FLN) in its struggle for Algeria’s independence from a stubborn French master. Fanon became an ardent writer for the revolutionary newspaper El Moujahid and a leading spokesman of the FLN. Shortly after completing his seminal work The Wretched of the Earth in 1961, Fanon passed away from tuberculosis at the age of 36.

Fanon’s posthumous fame as an anti-colonial theorist became focused on his one singular observation about violence during decolonization. ‘’Violence,” he argued, “is a cleansing force. It frees the native from his inferiority complex and from his despair and inaction; it makes him fearless and restores his self-respect.’’

Fanon maintained that decolonization “fundamentally alters” the colonized man’s sense of self: “It infuses a new rhythm, specific to a new generation of men, with a new language and new humanity. Decolonization is truly the creation of new men.” This observation about the new men formed through the therapeutic and instrumental use of violence has been consistently viewed as a malign and dangerous idea.

The novelty of Olsson’s film is that it readdresses this problematic. Notably, whether it is accurate to read Fanon as a “prophet of violence”—a reading which has dominated academic circles and conventional knowledge—and, whether violence is justified (as a means and as an end) in the struggle for liberation.

Concerning Violence, at once both an aesthetic and realist rendition of Fanon’s thought, humanizes the discourse on violence.

Nine Scenes of Decolonization

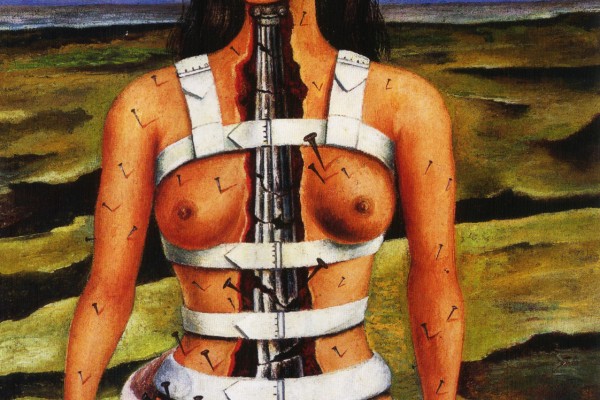

A momentous scene in the film is the footage of the one-armed black Venus, the Madonna of Mozambique. Her back is straight, shoulders raised and covered in white cloth—there is a mature dignity in her posture. But her head drops, melancholic eyes gaze into an inward distance. She is almost a child herself, with a child at her bare breast; and the child too is maimed, its leg amputated at the knee.

Olsson composes Concerning Violence out of a diversity of scenes like a composer conducts an orchestra: beneath the confusion and chaos there is a beautiful melody, a unity of expression in the images of decolonization. The chapters of the film confront the physical, psychological, social, political, and economic themes which Fanon articulated in his work.

One chapter progresses as the MPLA conduct a night raid in Angola in 1974 against a Portuguese military base. Another, entitled “Indifference,” presents an interview with a young South African professor who speaks of the five years he spent in jail and the lack of feeling that his liberation produced in him.

Later chapters deal with FRELIMO in Mozambique, there is an interview with PAIGC leader Amilcar Cabral in Guinea-Bissau, as well as with the revolutionary President of Burkina Faso Thomas Sankara in 1987, shortly before his assassination in a Western orchestrated coup.

One chapter, entitled “That Poverty of Spirit,” shows a Scandinavian missionary couple sheepishly propagating the civilization of African culture and values under the thin veil of Christianity. Another scene documents a mining strike in Liberia in 1966, and yet another confronts white settlers in Rhodesia.

Between these scenes, like a heavy drum, the words of Fanon beat across the screen in bold white font. We read:

“The settler makes history; his life is an epic, an Odyssey. He is the absolute beginning: “This land was created by us.” He is the unceasing cause: “If we leave, all is lost.” And all the while the native, bent double, more dead than alive, exists interminably in an unchanging dream.”

Fanon’s words are the negation of this colonizing narrative. Decolonization is the negation of this narrative in practice. Olsson’s film is a confrontation of this narrative, a contextualization of the dream. In decolonization the colonized peoples fight for liberation and assert their dream. The images of the film capture this assertion.

A Prophet of Violence

“Decolonization is a historical process. It cannot be understood, it cannot become clear to itself except by the movements which give it historical form and content. Decolonization, which sets out to change the order of the world, is, obviously, a program of complete disorder. But it cannot come as a result of magical practices, nor of a natural shock, nor of a friendly understanding.”

“Decolonization is always a violent phenomenon.”

Fanon was no prophet of violence, he spoke of what he saw and experienced. Violence always begins with the colonizer, who “brings violence into the homes and minds of the colonized subject.” During decolonization, it is this unceasing, unchecked, and destructive violence that is “appropriated” by the colonized.

Gayatri Spivak says in the preface to Olsson’s film that Fanon’s lesson for the colonized is to “use what the masters have developed and turn it around in the interest of those who have been inslaved or colonized.” Fanon’s lesson did not concern just violence. Here Spivak concludes that “Fanon would have been useful today.” Why?

The film Concerning Violence bears a message of hope, a dream, that is dressed in realism, in the real—or rather, undressed, naked, raw. This suffocating, naked hope bears heavy on our shoulders, is difficult to bear, for we have seen it cuckolded, corrupted, killed in the decades that have passed since independence.

Fanon hoped that “[the West would] not manage to divide the progressive forces which mean to lead mankind towards happiness by brandishing the threat of a Third World.” But by and large, the West and its puppets did manage to do so, to divide the progressive forces.

And it is for this very reason that so many ideas which Fanon articulated, yelled—hypotheses on decolonization, violence, identity, nationhood, to be addressed later by the likes of Cabral and Sankara—are still pertinent today and must be taken seriously.

I reiterate: we are all actors in the drama that has unfolded, and which consistently continues to play itself out. This is merely to say that we are not standing at the end of History, and whichever cause we choose to appropriate, we cannot remain indifferent.

The film ends with these words from the conclusion of The Wretched of the Earth:

“This huge task which consists of reintroducing mankind into the world, the whole of mankind, will be carried out with the indispensable help of the European peoples, who themselves have often joined the ranks of our common masters. To achieve this, the European people must first decide to wake up, and shake themselves, use their brains, and stop playing the stupid game of the Sleeping Beauty.”

Much has changed since 1961, but this message is still pertinent in 2014. Concerning Violence is an aesthetic articulation of the intellect, of a truth unmasked. It brings to life Fanon’s words through their embodiment in men and women, transmits them to us through their stories and expressions, in the language of their aspirations.

Whatever conclusions you may draw from the film, it is a collage of human experiences and systemic forces that is vital to the understanding our times.

Concerning Violence: Nine Scenes from the Anti-Imperialistic Self-Defence premiers in Quebec on Monday, November 10, in Montreal at Concordia University, hosted by Cinema Politica.