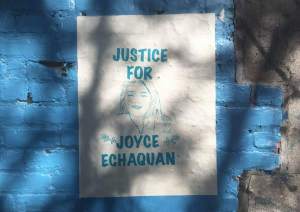

Nakuset Sohkisiwin, Native Women’s Shelter of Montreal executive director speaking out in support of the #JusticeForJoyce campaign. Photo by Abdelali Essaouist

“… they’re like, can you tell me about native people and justice? Like what justice? Has there been justice anywhere? I don’t see no justice. There is no justice. What are you talking about? Look what’s going on with the Mi’kmaw and the fish. Then you have the other land claims that are going on, and the RCMP that are beating the shit out of native people, like throughout Canada. It’s open season. So… justice. Yeah. ”

For months, Nakuset Sohkisiwin, Executive Director of the Native Women’s Shelter of Montreal and spokesperson for Resilience Montreal, has been wary of the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the help that the shelter received from supporters during the pandemic’s first wave, the municipal government itself has done little to ensure that Montreal’s most vulnerable will be safe as COVID-19 cases begin to rise again.

“We need to do better than we did the first time. There isn’t enough space in the shelters…This is basically a disaster waiting to happen.”

In urban centres like Montreal, 1 in 15 Indigenous people experience homelessness, in contrast to Canada’s overall population, in which 1 in 128 people are homeless Indigenous women also have the lowest income rate compared to any other group in Canada, while also experiencing violence at higher rates than the rest of Canada’s population. One cannot speak about housing injustice without also speaking about systemic discrimination and colonialism.

The call for confinement in Montreal presents a specific crisis for homeless people. As mandated indoor gathering numbers shrink in order to flatten the curve, shelter services like Resilience Montreal are forced to turn people away: “We can only let 60 people in the building right now at Resilience. We used to be able to double that. Where do the people go?”

Unless more systemic work is done, Nakuset is convinced that solutions such as those proposed recently in Toronto will not solve the root causes. Very few solutions prioritize what Nakuset believes is absolutely essential: a sense of community. And so, simply increasing funding and retrofitting hotels overlooks the core problems of homelessness among Indigenous people.

That sense of community has been under attack since European colonization began; colonization may have changed its form, but it persists all over these unceded territories popularly known to settlers as Canada. Most notably, the decades-long pattern of missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirits has been a clear example of ongoing colonial violence Very often, Indigenous people have become homeless by virtue of being caught between a rock and hard place. “The government keeps promising to build houses and never does. And then people have to stay with what [the government has] created for them because they’re not allowed to live in igloos anymore. That’s considered too savage.” For instance, one of the ways that Canadian governments systematically disenfranchised the Inuit is by slaughtering their sled dogs, known as qimmiit, to force them to abandon their traditional practices.

“So they’ve become dependent on the government while they’re waiting for them to build new houses. They come to Montreal and there’s so much racism in Montreal. We hear time and time again, ‘Oh, I don’t rent to Inuit because you’re all a bunch of drunks,’ and that is a blanket statement. It’s almost like whatever obstacles [are] in your way, you’re not going to get through it unless you are literally teamed up with some kind of advocate or frontline worker to challenge that person in their perspectives. And this happens when they go to the hospitals, they get derogatory comments. When they go to find an apartment, when they try to find a job, when they try to have a conversation with the police or the police are racial profiling them. Unless you are literally standing with them all the time, people typically take advantage. And, as Indigenous people, we are sort of used to that behavior, which is a horrible thing to be used to.”

Second-Stage Housing Project

After ten years of planning, the Native Women’s Shelter will be building twenty-three second-stage housing units for Indigenous women and children with Bâtir son quartier. The hardest part was finding a location that was in the city and very accessible.

“I know that as soon as we announce the twenty-three units, in two seconds they’ll be filled,” says Nakuset. “Great, and then what? What about everybody else?” But, as Nakuset has said, simply providing homes is not an adequate solution: “We want housing where you have people who are there to support you.”

Unlike most shelters, Nakuset’s facilities will include an addiction worker and a family care worker on location once per week, as well as psychologists, therapists, and elders present every day for when the women come out of their fully furnished apartments.

“They can come into sort of the common area and be like, so and so is here, you can sign up for a session. And if they don’t want to, you don’t have to. They can go and study or get a job or whatever it is they want to do, but [the workers are] always there for them. So if they’re in a crisis, they don’t have to run around the city and wonder ‘Who am I going to talk to about this?’. It’s set up for you.”

What’s more, most shelters have designated meal times, which can be inaccessible. At the Native Women’s Shelter, “Food is [ready] all the time because if you’re on the streets and you’re having a difficult time and you get into some kind of run-in with the police or [a] gang or God knows what, and you come to us and you’re hungry, we can guarantee you some food. Like, seriously. Like, it’s the minimum.”

“We’re having a community space so that we can have ceremonies together and we can have celebrations together and we can have someone come in and be a speaker and do teachings and whatever and have arts and crafts or whatever.”

The sense of community makes all the difference. In most housing projects, people are simply shoved into typically dreary and very clinical-looking apartments, which technically solves the issue of homelessness while nevertheless failing to tackle the root of the issue. Many homeless people, says Nakuset, are not ready to live alone. “And then [the women say], ‘Now what? Oh, wait, I think I’m going to go back to the street and just sit on the sidewalk, because that’s where I’m comfortable and I can actually have conversations with people.’ OK, so they leave their apartment.”

“If you don’t deal with the trauma about why they were homeless to begin with, then it’s just a Band-Aid. It’s temporary,” she adds. The pandemic has exposed short-term solutions as incapable of withstanding crises, and the most vulnerable among us continue to bear the brunt.

“How come there’s no other organization that’s out there with all their stuff since COVID hit? We’re the only ones.” Nakuset hopes that other services will lead by her example.

“I’m very optimistic about the future if that makes any sense. I’m like, bring it on. I’m not hopeful with society changing its ways, but I am optimistic about meeting all the challenges that come my way and find a way to mow through them.”

***

Please consider donating to the Montreal Native Women’s Shelter.