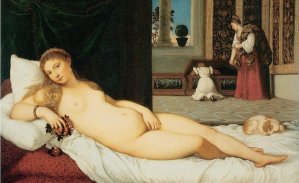

“Women’s work” has long been stigmatized in Western society. Though we see the necessity in jobs associated with empathy and maternal instinct, we are quick to characterize individuals occupying certain “feminized” workspaces as less-important or even inconsequential - including those involved in sex work. Accordingly, we view them as either powerless or in possession of a distinctly “feminine power” that is simultaneously feared and admired.

In her book, King Kong Theory, Virginie Despentes describes how we view women in pornography, saying “[viewers] are furious that these girls have performed exactly what they want to see. Masculine grace and coherence in a nutshell, “Give me what I want I beg you, so that I can spit in your face for doing it.” Women are expected to possess this mysterious “feminine power”, and are simultaneously shamed for complying with society’s fetishization of it.

It seems that in the search for power, women must choose between: A) attempting to carve out a space for ourselves in a world that does not welcome us (a world favouring men) or B) a power that belongs distinctly to our gender but gives others permission to degrade us. Women in business and politics are seen as trail-blazers: among the first to “take the road less travelled,” but those working in what is arguably “the world’s oldest profession” are commodified, demonized, and shat on.

Clarissa Pinkola Estes explains why in her book Women Who Run with the Wolves. She writes, “this early training to “be nice” causes women to override their intuitions. In that sense, they are actually purposefully taught to submit to the predator.” We are taught to take pleasure in our own powerlessness because it preserves the status quo. Men are on top, they are naturally strong, and we are naturally weak; any power involuntarily bestowed upon us - including our sexuality - is dirty and never to be capitalized on. This system continuously devalues “women’s work” and “women’s power” and reaffirms the supposedly innate, and rightful power of our male counterparts.

Transgender women face immense levels of marginalization and objectification. By virtue of being trans, these women are often unwelcome in traditional workspaces, and so often feel as though sex work is the only viable career path. It is estimated that 10.8% of transgender individuals have engaged in sex work, and women who lose their jobs because of transphobia are three times more likely to go into sex work - a whopping 19.9% more likely. Trans-women occupy an especially low position in the gendered hierarchy of power, often facing exclusion from both sides.

Later in her book, Despentes details the sudden surge in power she felt during her early days as a prostitute, stating that “some American sex workers use the word ’empowerment’ when talking about their experiences as hookers. A rise in power. I immediately loved the impact I made on the male population…There was an immediate change as soon as I put on my ultra-feminine uniform: sudden confidence as with a line of coke.”

To her, prostitution was a way to control the conditions of work while simultaneously exploring her sexuality. By embracing traditional norms of femininity, in a somewhat rebellious fashion she was able to reap the rewards of a system rigged against her, against women who publicly own their sexuality.

Women in traditionally male-dominated fields are, of course, heroic: daring to go where no woman has gone before. Perhaps power will become less gendered as more of us pursue this lifestyle. But sex workers (and women in other precarious professions) are lion-hearted nonetheless for sticking with a trade that labels them as “lesser.”

What the patriarchy tells us is clear: there is no way to pursue power as a woman and be respected for it. We are either taking something that doesn’t belong to us, or fulfilling our role as objects. The lesson here then is not to shame anyone for doing what empowers them, or even what disempowers them. Empowerment implies self-determination, which can never be separate from gender until we live in a world without gender discrepancies.

Works Cited

Despentes, V. (2010). King Kong theory. New York: Feminist Press at the City University of New York.

Éstes, C. P. (1995). Women who run with wolves: Myths and stories of the wild women archetype. New York: Ballantine Books.