Analogies overly animate the urban life. The city can compare to an ecosystem, a beehive, a large star, and since the growth of biology in the 19th century, a living organism. We embellish the vital city as if it eats, breaths and defecates; but in the cold light of reality, the city is quite dead. If the streets are like my blood, their fluid has chilled and clotted. If the buildings are my cells, then the basic unit of life has been cemented and industrialized. In fact, I am still waiting for the apoptosis of 1960s architecture. Strip away the analogy and I see this death: impoverished city-dwellers on the cusp of survival, waterways excessively usurped in the name of industry and impurely excreted. Even when my body deceases, it will be incinerated to dust or quarantined in concrete slabs.

We, the living city, disconnected from our organic life when we traded corn for cubicles. This is not a problem of ecology. It is a problem of design.

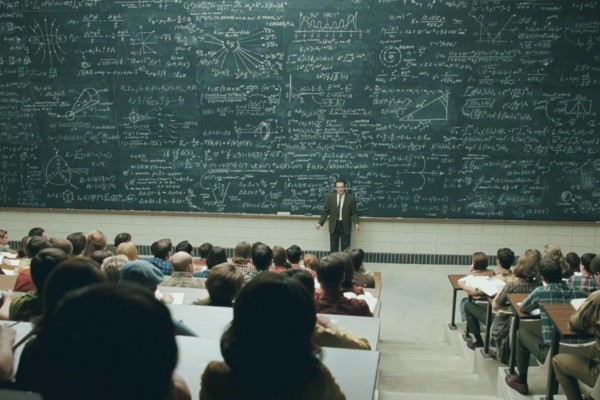

The opportunities for symbiosis and connection both attract us to cities and generate commerce, science, art, and without any hyperbole, progress. The engine power lies in the city’s design, which pre-determines certain interactions, whether they be between other humans, nature, technology, or ideas; for a simple example, an outdoor classroom creates spaces for children to connect with nature while an indoor classroom does not. To redesign life and interaction in the city, we must design with life in mind and in hand. In the following projects, biodesign forces us to reassess the city and perhaps resurrect its remains.

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-dxU6Hw2dMt8/UsxHVNACWKI/AAAAAAAAASk/k15-srIGpdY/s1600/2+pedrera+cultivos+bis+oscura.jpg

The design group Genetic Architecture fused biological techniques and architectural design in the creation of bioluminescent trees. The team genetically inserted the fluorescent protein from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria into seven lemon trees. These trees illuminate at night, replacing street lights while cutting city costs and energy use. Additionally, planting trees rather than metal poles forms a greener, more oxygen-rich space.

Mighty Mushrooms

The humble mushroom will revolutionize material, death, and cleansing. The mushroom’s structural foundation, mycelium, has numerous natural qualities which bear utility: water absorbent, flame retardant, and insulative; it has been made into bowls, chairs, packaging, and even a large structure called Hy-Fi at MoMA PS1 in Long Island City, New York.

Mushrooms can also recycle, among many things, our bodies. Artist Jae Rhim Lee created a mushroom burial suit for a green funeral; here she describes the suit’s makeup:

The first prototype of the Infinity Burial Suit is a body suit embroidered with thread infused with mushroom spores. The embroidery pattern resembles the dendritic growth of mushroom mycelium. The Suit is accompanied by an Alternative Embalming Fluid, a liquid spore slurry, and Decompiculture Makeup, a two-part makeup consisting of a mixture of dry mineral makeup and dried mushroom spores and a separate liquid culture medium. Combining the two parts and applying them to the body activates the mushroom spores to develop and grow.

Traditional death and burial practices eliminate our capacity to decompose and recycle back into the Earth. This suit moves towards a more ecological spirituality and a more free death.

Concrete remains one of the most ubiquitous building materials. There is, however, a crack in its utility: it cracks. When this occurs, water can seep through, corrode the underlying steel, and jeopardize a structure’s integrity, and repairing cracks can be extremely difficult if underground or containing liquids. Microbiologists at the TU Delft in the Netherlands added an alkaphilic bacteria to traditional concrete and renamed the material “Bioconcrete”. When water seeps into a crack, the bacteria activates and produces limestone to reseal the gap. A longer living material boasts economic returns.

We know the implications of a breathing organic city: it’s safer, healthier, and happier. The push for greener urban life has begun, but should not continue without city design in mind. I am, though, struck with questions of practicality: Are these changes economically feasible or overly radical? How do city planners incorporate biodesign into historic cities like Paris? And should legal and ethical preparation and pre-emptive regulation begin now?

These necessitate an evaluation of biodesign within the context of law, ethics, and the economy, but just an introduction to its core features has already posed contemporary questions and touched unfamiliar systems.

When the cubicle grows out from corn and the walls breath in unison with the street, then these growing urban centers will animate our lives, and not the other way around.

-A.W. Sully

Featured Image: http://infinityburialproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/IWAB_Installation_sm.jpg